A horse suffering from laminitis often stands with his front feet parked out in front and his hind feet farther under his body than normal, trying to find a comfortable place to put his weight. | © Bob Langrish

A horse suffering from laminitis often stands with his front feet parked out in front and his hind feet farther under his body than normal, trying to find a comfortable place to put his weight. | © Bob LangrishIt’s dinnertime, but your horse isn’t pacing his stall or waiting at his feed bucket. He’s planted in a corner with his front feet parked forward, shifting his weight from one to the other. When you check his front hooves, they feel warm. He’s showing signs of laminitis, a potentially devastating disorder in which the bond between the hoof wall and the main bone of the foot weakens or gives way.

Laminitis can end your horse’s career or cause such severe, unrelenting pain that euthanasia is the only choice. The statistics are grim. Surveys show that this disease affects about 1 percent of all U.S. horses at any given time and leads to death or euthanasia in about 5 percent of cases. Its victims have included renowned racehorses, backyard ponies and every equine type between.

Veterinarians have wrestled for years with questions about how laminitis develops and how it should be treated. Now, thanks to an international research effort, they’re beginning to get answers. “There is progress on all fronts,” reports James Belknap, DVM, PhD, DACVS. A professor of equine surgery at the Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Dr. Belknap is on the front lines of the fight against laminitis. In this article, he explains how research is leading to advances in treatment and prevention.

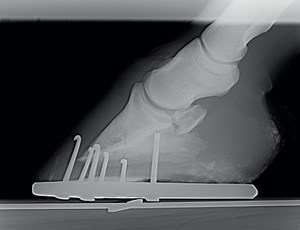

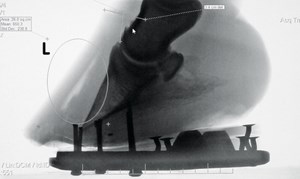

A radiograph shows the normal position of the coffin bone. | © Courtesy, Monocacy Equine Group

A radiograph shows the normal position of the coffin bone. | © Courtesy, Monocacy Equine Group In the X-ray, the circle indicates laminar separation and the coffin bone has rotated. | © Dusty Perin

In the X-ray, the circle indicates laminar separation and the coffin bone has rotated. | © Dusty PerinInside Story

Laminitis is more common in the front feet (usually both), but the hind feet can be hit, too. These are the classic signs:

• A strong, bounding digital pulse. Find it at the pastern, just below the outer side of the fetlock joint. Normally the pulse here is faint, almost undetectable. A strong pulse indicates inflammation, and a bounding pulse in both front feet is often the first sign of laminitis.

• Heat in the hoof, another sign of inflammation.

• Lameness. The horse may move stiffly and especially resent being turned in a tight circle, or he may be reluctant to move at all.

• An odd stance. He may stand with his front feet parked out in front and his hind feet farther under his body than normal. When all four feet are involved, the stance may be “camped out” (forelimbs farther forward and hind limbs farther back).

• Paddling. The horse may shift his weight constantly from one foot to the other, trying to find a comfortable place to put his weight.

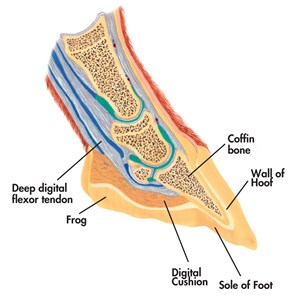

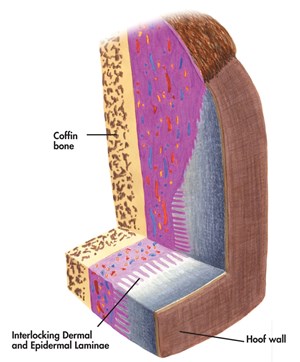

One reason laminitis so often ends badly is that internal damage begins long before these signs show up. In a normal foot the main bone—the coffin bone, also called the distal phalanx—is suspended behind the hoof wall by delicate accordion-like structures called laminae. Inner (dermal) laminae on the bone side mesh like interlocking fingers with outer (epidermal) laminae on the inside of the hoof wall.

The bond formed by the laminae suspends the entire weight of the horse as it comes down the bony column of the leg and is carried out to the hoof wall. When this vital bond fails in laminitis, the coffin bone can tear loose from the hoof wall. The bone presses down on soft tissues below, causing excruciating pain and sometimes even punching through the sole.

In a normal foot, the coffin bone (distal phalanx) is suspended behind the hoof wall by laminae. Inner (dermal) laminae on the bone side mesh like interlocking fingers with outer (epidermal) laminae on the inside of the hoof wall. | © Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy and Common Disorders of the Horse

In a normal foot, the coffin bone (distal phalanx) is suspended behind the hoof wall by laminae. Inner (dermal) laminae on the bone side mesh like interlocking fingers with outer (epidermal) laminae on the inside of the hoof wall. | © Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy and Common Disorders of the Horse The bond formed by the laminae suspends the entire weight of the horse as it comes down the leg and is carried out to the hoof wall. | © Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy and Common Disorders of the Horse

The bond formed by the laminae suspends the entire weight of the horse as it comes down the leg and is carried out to the hoof wall. | © Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy and Common Disorders of the HorseDepending on the severity of the case and hoof conformation, three types of coffin-bone displacement can occur:

• Rotation: The laminae at the toe detach, allowing the tip of the coffin bone to rotate down. The deep digital flexor tendon pull on the bone encourages rotation.

• Symmetrical sinking: The laminae are severely affected around the entire foot, letting the entire coffin bone sink toward the ground.

• Medial or asymmetrical sinking: More rarely, the laminae give way on the inside or outside of the foot so the coffin bone sinks to that side.

It’s long been known that some horses are prone to laminitis and that certain events—severe colic, acute infections, gorging on spring grass or sweet feed, carrying excessive weight on one leg—can trigger an attack. The hows and whys have been much less clear, but researchers are starting to find out. The critical events take place at a microscopic level in the foot, along a thin layer of connective tissue called the basement membrane

The basement membrane lies between the inner laminae and a layer of cells (dermal basal epithelial cells) on the hoof side. Laminar attachment depends entirely on microscopic protein complexes called hemidesmosomes that connect the basal epithelial cells to the membrane. “These same protein complexes bind the basal epithelial cells of our skin to underlying connective tissue,” Dr. Belknap says. “The difference is that our skin doesn’t have to support a thousand pounds of weight.” Skin cells must be able to detach and migrate in events such as wound healing, he adds. In humans, research shows, they accomplish this through cell-signaling pathways that regulate the production or breakdown of hemidesmosomes and by producing enzymes that can break down tissue in the basement membrane.

Compared to the hoof trimming from a normal hoof, a horse’s laminitic hoof shows separation of the inner and outer laminae as it grows out. | © CLiX Photography

Compared to the hoof trimming from a normal hoof, a horse’s laminitic hoof shows separation of the inner and outer laminae as it grows out. | © CLiX PhotographyWhy does this esoteric science matter? “Veterinary researchers now consider it likely that the many different conditions that result in laminitis do so by affecting the regulation of the hemidesmosome attachment,” Dr. Belknap says. If the pathways that lead to damage can be pinned down, perhaps they can be blocked.

Laminitis Three Ways

There are three main types of laminitis, Dr. Belknap says. “All three follow the same course to a degree, but there are differences in the way they develop.”

Sepsis-related laminitis begins with the absorption of bacterial toxins. The source of the toxins may be an infected organ (the lungs in pneumonia or the uterus in metritis or a retained placenta). More often, it’s a GI tract compromised by loss of blood supply, as in colon torsion, or by inflammation, as in grain overload or colitis. Then bacterial toxins pass through the intestine wall and set off a system-wide response, activating white blood cells that release a flood of substances called inflammatory mediators. The result is similar to severe sepsis in humans, in which overwhelming inflammation can lead to organ failure. In horses, inflammation is greatest in the laminae.

There are still questions about exactly how the damage occurs, but a picture is emerging. “The severe inflammation in the laminae likely sets up a cascade of events resulting not only in the disruption of the cellular signaling in the laminar basal epithelial cells, affecting their adhesion properties, but also the release of enzymes that break down the basement membrane,” Dr. Belknap says.

Endocrine-related laminitis takes a slightly different course. Horses with equine metabolic syndrome and equine Cushing’s disease (pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction) are at high risk for this form. Both conditions involve insulin resistance, a condition that makes it hard to process carbohydrates in feed. Insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas, allows cells in the body to regulate glucose levels and to convert glucose to energy. In insulin resistance, the cells don’t use insulin properly so the horse must produce more insulin to move glucose into cells.

“These horses develop incredibly high levels of circulating insulin,” Dr. Belknap notes. And while other factors may be involved, insulin appears to be the driving force in this type of laminitis. Recent work by Dr. Chris Pollitt’s Australian Equine Laminitis Research Unit suggests that excess insulin may activate a process called growth-factor signaling in the laminae. This disrupts not only the adhesion properties but also the cytoskeletons of the cells so the cells lose their normal structure and stretch. “It’s usually not a crash-and-burn event as occurs in sepsis-related and supporting-limb laminitis,” says Dr. Belknap. “It’s commonly more insidious.”

Supporting-limb laminitis affects horses who are laid up with severe leg injuries, like fractures. The horse spares the injured limb by putting more weight on another, usually the opposite limb. The longer this goes on, the greater the risk that laminitis will develop in the supporting limb—and the attack is often sudden and severe. “The horse can seem fine for several weeks and then suddenly suffer catastrophic failure,” Dr. Belknap says. It’s estimated that half of horses who develop this type of laminitis are euthanized.

Work from both Dr. Belknap’s lab and Australian researcher Andrew van Eps indicates that circulation in the supporting limb is a key factor. When blood flow to the foot is restricted, cells are starved for oxygen, a condition called hypoxia, and the laminae can be affected. Drs. van Eps and Belknap have both recently found evidence of hypoxia in laminar tissue of horses with supporting-limb laminitis, but Dr. Belknap says that his collaborator in Australia has really moved the field forward with his findings. “Van Eps showed that it’s not the pressure of excessive weight-bearing so much as lack of movement that causes hypoxia in these horses,” Dr. Belknap says. “As soon as the limb moves, circulation to the foot is restored and more oxygen reaches the tissues.”

However it starts, laminitis is always an emergency.

When a horse gorges himself on sweet feed, it can compromise his GI tract and lead to septis-related laminitis. | © Stacey Nedrow-Wigmore

When a horse gorges himself on sweet feed, it can compromise his GI tract and lead to septis-related laminitis. | © Stacey Nedrow-Wigmore A classic sign of a horse with laminitis is a strong, bounding digital pulse just below the outer side of the fetlock joint. | © Stacey Nedrow-Wigmore

A classic sign of a horse with laminitis is a strong, bounding digital pulse just below the outer side of the fetlock joint. | © Stacey Nedrow-Wigmore It’s long been known that certain events, including gorging on spring grass, can trigger laminitis. | © Sandra Oliynyk

It’s long been known that certain events, including gorging on spring grass, can trigger laminitis. | © Sandra OliynykWhat to Do

Early, aggressive treatment can limit damage and may save your horse’s life, so call your veterinarian immediately if you see signs. If you know the horse experienced a triggering event—he broke into the feed room and stuffed himself with grain, say—call even before you see signs. In septic laminitis there’s typically a lag of 24 to 72 hours between the triggering event and the first signs, but the inflammatory response begins almost immediately. The faster you can halt it, the better your horse’s chances will be.

No single treatment works in every case of laminitis, but researchers are learning more about what’s likely to work best in each of the three types.

Make it cold: Standing the horse in ice water is an old-time remedy, but now veterinarians have ramped up the treatment and discovered how helpful cryotherapy can be. The new protocol calls for icing affected limbs continuously for 48 to 72 hours straight to induce hypothermia. You couldn’t tolerate this, but your horse can, and research shows that it can significantly reduce damage in sepsis-related laminitis.

“Cryotherapy is protective when it’s started before signs appear and even later, started when the horse first shows signs of lameness. It won’t save every horse, but there is a tenfold increase in risk if the horse is not iced,” Dr. Belknap says. “We know less about the effects of cryotherapy in endocrine-related and supporting-limb laminitis.” In those types there is no identifiable, immediate triggering event, and a horse can’t be kept on ice for weeks. But icing may still help when signs appear. “It certainly won’t hurt, and I would use it,” he says.

Keeping the horse’s feet and lower limbs submerged in crushed ice around the clock is labor-intensive, he adds. A new ice boot developed by Soft-Ride with the input of Drs. Belknap and van Eps may help. Ice wraps aren’t as effective; the foot needs to be immersed in ice water.

Ease pain and inflammation: The go-to medications for this are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, mainly flunixin meglumine (Banamine®) and phenylbutazone, which reduce pain as they break the cycle of inflammation. The dosage usually starts high and is adjusted as severe signs (pulse, pain, heat) ease.

Support the feet: To take strain off the laminae, remove the horse’s shoes, which put most of his weight on the hoof wall. Support the sole by taping on commercial supports or foam pads. Any exercise could cause the laminae to give way, so keep the horse in a stall. Bed it deeply (or provide soft but supportive footing, such as sand) to provide cushion and encourage him to lie down as much as possible.

X-rays are essential to see if the coffin bone is displaced. If they show rotation, the vet may advise raising the heels with taped-on pads and resilient putty. This reduces the pull of the deep flexor tendon on the coffin bone. If supports don’t stabilize the bone, a cast may do the trick. In clinics, a sling is sometimes used to take weight off the horse’s feet.

The next few weeks are critical. If you can halt displacement in that time, the foot will usually stabilize. Your vet will take follow-up X-rays to see what’s happening in the foot. Meanwhile, monitor your horse closely and call your vet if you see

• the return of heat in the feet or a bounding digital pulse.

• signs that your horse’s pain is increasing. Watch him in his stall: If he moves around comfortably when he’s not resting, he’s probably not in too much pain. If he becomes less willing to move, be concerned.

• cracking at the coronary band or cracking or a bulge on the sole. These signs signal an emergency—the coffin bone is displacing.

Research shows that icing limbs affected by laminitis continuously for 48 to 72 hours to induce hypothermia can significantly reduce damage in sepsis-related laminitis. A new ice boot developed by Soft-Ride may help with the labor-intensive work of keeping a horse’s feet and lower-limbs submerged in crushed ice around the clock. | Courtesy, Soft-Ride

Research shows that icing limbs affected by laminitis continuously for 48 to 72 hours to induce hypothermia can significantly reduce damage in sepsis-related laminitis. A new ice boot developed by Soft-Ride may help with the labor-intensive work of keeping a horse’s feet and lower-limbs submerged in crushed ice around the clock. | Courtesy, Soft-Ride To take strain off the laminae, remove the horse’s shoes, which put most of his weight on the hoof wall. Support the sole by taping on foam pads or commercial supports. | © Practical Horseman

To take strain off the laminae, remove the horse’s shoes, which put most of his weight on the hoof wall. Support the sole by taping on foam pads or commercial supports. | © Practical Horseman Any exercise could cause the laminae of a laminitc horse to give way, so keep him in a stall. Bed it deeply to provide cushion and encourage him to lie down as much as possible. | © Arnd Bronkhorst

Any exercise could cause the laminae of a laminitc horse to give way, so keep him in a stall. Bed it deeply to provide cushion and encourage him to lie down as much as possible. | © Arnd BronkhorstThe Road Back

Once the foot is stable, the long process of repairing the damage can begin. It can take a year for healthy new hoof to fully grow in, and the laminae won’t be firmly attached until then.

Corrective shoeing can help the hoof grow out as close as possible to its normal position in relation to the bone. Work as a team with your vet and an experienced farrier to devise a long-range plan tailored to your horse’s needs. Your vet will take follow-up X-rays to guide the work. Each case is different, Dr. Belknap says, but most recovering horses do better with shoes than without as long as the shoes fit the case and provide support for the sole. The options include:

• customized heart-bar, egg-bar or other traditional shoes combined with various types of pads.

• commercial shoeing systems designed for laminitis recovery. Several of these use bevel-front aluminum shoes set back at the toe to relieve the stress of breakover with pads and support materials to protect the sole and raise the heels as needed.

• full-rocker designs like the Seward Clog, which allow easy breakover in any direction. “The clog shoe can make a huge difference as a tool to bring the distal phalanx back into alignment,” Dr. Belknap says, but it’s not a shoe for long-term use. “It’s a step to get back to a regular shoe—use it two to four months, six at most.”

• Soft-Ride Comfort boots, which can be fitted with gel orthotics and used with or without a rocker bottom.

When can the horse get out of the stall? When he’s past the acute stage and moving comfortably in his shoes, ask your vet if you can hand-walk or turn him out in a small paddock with level, soft footing. Moving around improves circulation and may promote recovery, but doing too much too soon definitely has risks. A horse with severe displacement and massive damage to the laminae will obviously need to be in a stall longer than a mild case. Wait until enough healthy hoof has grown in to support the horse’s weight.

The outlook for full recovery is best in mild cases. If there’s no displacement, the horse may be able to begin light work in three or four months. The chances for return to full work are slim if the coffin bone sinks severely or rotates 15 degrees or more.

Corrective shoeing can help a laminitic hoof grow out as close as possible to its normal position in relation to the coffin bone. An aluminum egg-bar or other traditional shoe combined with various pads protects the sole and raises the heels. | © Dusty Perin

Corrective shoeing can help a laminitic hoof grow out as close as possible to its normal position in relation to the coffin bone. An aluminum egg-bar or other traditional shoe combined with various pads protects the sole and raises the heels. | © Dusty Perin This natural-break shoe with frog support and an Equi-Pak filled pad absorb shock and concussion. | © Dusty Perin

This natural-break shoe with frog support and an Equi-Pak filled pad absorb shock and concussion. | © Dusty Perin A full-rocker design shoe like the Seward Clog helps support the sole while allowing for easier breakover. It can make a big difference to bring the coffin bone back into alignment. | Courtesy, Hopeforsoundness.com

A full-rocker design shoe like the Seward Clog helps support the sole while allowing for easier breakover. It can make a big difference to bring the coffin bone back into alignment. | Courtesy, Hopeforsoundness.comLingering Problems

A horse who has had one episode of laminitis is at risk for more. That’s especially so for horses with endocrine-related laminitis. “Management is critical for these horses,” Dr. Belknap says. They need a diet low in sugars and other carbohydrates with strictly limited grazing. Obesity contributes to equine metabolic syndrome, and exercise can help keep weight down. If the horse isn’t sound enough for that, the synthetic thyroid hormone levothyroxine may help him lose weight. Some research suggests that the drug metformin may help lower insulin levels. Horses with equine Cushing’s disease can benefit hugely from the drug pergolide.

Even without a recurrence, a horse can have chronic problems after laminitis. Uncorrected rotation can cause the hoof wall to dish at the toe, strain the laminae and set the stage for infections in the foot. The pressure of the coffin bone on the sole can make him chronically sore and lead to deep abscesses.

A lot can be done to help. Your vet can flush deep abscesses that can’t be reached by soaking. Your farrier can bevel the front of the horse’s foot to reduce strain on weak laminae and apply shoes and pads that protect the sole. Still, a horse who has chronic discomfort may need anti-inflammatory drugs for an extended time.

When trimming and shoeing don’t correct rotation, an operation called tenotomy sometimes helps. The surgeon cuts the deep digital flexor tendon to relieve its pull on the coffin bone. The horse will need a year of intensive aftercare, starting with three months of stall rest while the tendon heals and corrective shoeing slowly brings the bone back to a more normal angle. These horses seldom return to full work, but they are often pasture sound for at least several years.

What’s Next?

Laminitis has claimed high-profile victims. The best known in recent years may be the 2006 Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro, who fractured his right hind leg in the Preakness Stakes and was euthanized eight months later after developing supporting-limb laminitis. Such cases have helped spur efforts to find better treatments.

Laminitis research is ongoing at over a dozen universities and equine centers in the United States, Australia, Britain and other countries. The American Association of Equine Practitioners, the Animal Health Foundation, Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation and many other groups are supporting the work. And the efforts are getting results.

“In cryotherapy, we have the first treatment ever shown to be effective in septis-related laminitis,” says Dr. James Belknap. “We are getting there on endocrine-related laminitis. We know that it’s insulin related, and we have identified critical metabolic pathways that are involved. Researchers are investigating the use of drugs to block those pathways. And we’ve learned how important management is for these horses.”

For sepsis- and endocrine-related laminitis, it’s likely that the answer will be polytherapy—multiple treatments, rather than a single fix, he says. “For supporting-leg laminitis we need something prophylactic to prevent the sudden and catastrophic separation that’s typical with this form. It’s probably going to be mechanical, rather than a drug.” One possibility is a pneumatic shoe, currently in development, with an air bladder that keeps the foot in slight but constant motion to maintain the circulation.

This article originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of Practical Horseman.