There are two definitions to the word “surefooted,” each of which contributes to a superior riding horse. The first is “confident, not prone to errors in judgment or action.”

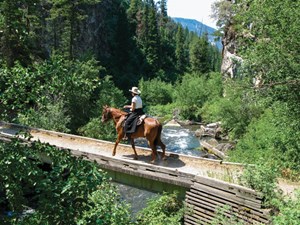

Credit: Kent and Charlene Krone When the going gets tough, give your horse his head, so he has the freedom to watch for obstacles, and use his head and neck for balance. Shown is seasoned gaited-horse owner Charlene Krone aboard her Missouri Fox Trotter gelding.

Credit: Kent and Charlene Krone When the going gets tough, give your horse his head, so he has the freedom to watch for obstacles, and use his head and neck for balance. Shown is seasoned gaited-horse owner Charlene Krone aboard her Missouri Fox Trotter gelding.Owners of Icelandic Horses, Kentucky Mountain Saddle Horses, Rocky Mountain Horses, Tennessee Walking Horses, Mangalarga Marchadors, and Missouri Fox Trotters, among others, regularly comment on their horses’ tendencies to instinctively choose the best path.

The other meaning, “not likely to stumble,” is a result of that good judgment and requires the physical ability to carry it out.

You might be surprised to know how many factors affect your gaited horse’s surefootedness and just exactly what you can do to preserve it.

Back when gaited horses were first selectively bred, the advantage of a smooth ride was instantly evident.

But breeders in regions with, shall we say, challenging terrain — the volcanic interior of Iceland, the rugged Appalachian Mountains, or the swamps and slopes of South America — noticed something else those extra gaits afforded. A horse with a range of gaits negotiated hazardous footing more easily and effectively than one with limited “gears.”

For instance, the Kentucky Mountain Saddle Horse exhibits four gaits: a smooth, flat walk or trail walk; an ambling gait (between 2 and 5 miles per hour); a distinct singlefoot called the pleasure gait (between 10 and 14 miles per hour); and the canter. In these gaits, at least one foot is on the ground at all times.

Head First

For most gaited horses, anything more than rare missteps to occasional stumbling should be taken as a signal that something is wrong, physically or mentally. After all, your horse wants to keep on his feet. In his 57-million-year evolutionary memory, hitting the ground is synonymous with being eaten.

So what does it take for your horse to be surefooted, even in treacherous terrain?

Here’s a rundown.

Credit: Andrea Barber Properly condition your gaited horse. An out-of-shape, fatigued, muscle-sore horse is likely to drag his toes, avoid raising his feet high enough to clear obstacles, stumble, and be inattentive. Shown are well-conditioned Icelandic Horses.

Credit: Andrea Barber Properly condition your gaited horse. An out-of-shape, fatigued, muscle-sore horse is likely to drag his toes, avoid raising his feet high enough to clear obstacles, stumble, and be inattentive. Shown are well-conditioned Icelandic Horses.? A calm, observant mind. Your horse’s mind directs his foot placement. If he’s anxious or distracted, he’s likely to forget what’s happening at the end of his legs. A horse that fights his rider is also likely to misstep, especially a young, green horse unfamiliar with trails and other horses.

But a mentally focused horse will watch his footing intently when the going gets rough, nose nearly to the ground, if necessary.

? Soundness and condition. These attributes are especially important while crossing demanding terrain.

? Balanced conformation. A surefooted horse has straight, sturdy legs of sufficient bone, and tough, well-shaped hooves. His soles are concave, and his frogs are fleshy and healthy. He’ll have a medium to short, strong back and a medium to slightly narrow chest to balance his load while controlling footfalls. Good bone structure is the framework over which all muscle and condition is built, and a horse can only excel within the limits of that framework.

? Good vision. Your horse’s vision guides his steps. “Good eyesight is a must,” explains high-country rider and Tennessee Walking Horse breeder William J. Erickson. “A horse with vision problems can easily misjudge where he places his feet. Floaters or other eye problems can cause a horse to ignore things he should see or react to things that aren’t even there.”

Best Foot Forward

The steps your horse takes are only as solid as the hooves that support him. Absorbing as much as 310,000 pounds of pressure per hoof (according to www.horseshoes.com, as measured in galloping racehorses), they’d better be as structurally sound and healthy as possible.

? Provide regular hoof care.To improve your horse’s hoof health, apply hoof moisturizers in dry weather, feed biotin and calcium supplements, and schedule regular farrier care. Brian Massingham is an avid trail rider and a farrier with more than 25 years’ experience shoeing all kinds of horses, including those for the United States Forest Service in the Cascade Mountains of Western Washington.

He stresses the importance of regular trimming and shoeing. “Keep your horse’s hooves trimmed every six to eight weeks, and think ahead,” Massingham says. “That means if you have a trail ride planned five weeks into your trimming/shoeing schedule, have the farrier out earlier, rather than later. The longer a horse’s toes grow, the more apt they are to cause him to stumble. Long toes with low heels are a common cause of stumbling.”

? Trim naturally. Trim to what’s natural for your horse, Massingham maintains, although he notes that slightly higher heels generally enhance agility. “How much is enough and how much is too much depend on [the opinion of] an experienced farrier and the needs of your individual horse,” he cautions.

Massingham also notes that long toes on the hind feet can affect overreach, which some may find desirable in the quest to manufacture gait, but that can lead to the horse striking his forelegs with his hind feet. “They can also cause a horse to drag his toes, and that can make him stumbly,” he says.

? Shoe correctly. Many stumbling problems are caused by improper shoeing, Massingham explains. He sometimes recommends rolling the toes or rocking them for easier breakover. And while not every horse needs shoes, he cautions that “heels wear down so much faster without shoes that most horses, especially regularly ridden gaited horses, need shoes for protection.

“It’s a red flag when a horse’s hooves land toe-to-heel,” he continues. “It’s a sign the horse is hurting somewhere. And even if he’s not lame or stumbling yet, he will be. The time to get him checked out is before a slight problem becomes a big one.”

? Evaluate foot soreness. Finally, have a qualified farrier evaluate any sources of foot soreness, such as an unbalanced trim job, a too-close trim, or early signs of laminitis or navicular disease. Back that up with a visit to your veterinarian. Look carefully for abscesses and stones lodged in the hoof, which are sometimes difficult to detect right away. A sore-footed horse is unlikely to remain a surefooted horse.

Rider Error

Too often, rider error jeopardizes a horse’s safe and certain path. Here’s how to help your horse stay steady.

? Check tack fit. Ill-fitting tack can lead to soreness and compromise surefootedness.

? Ride with a balanced seat. Listing to one side, or leaning forward or backward, can throw off your horse’s center of gravity and keep him constantly readjusting for balance instead of watching the trail ahead.

? Trust your horse’s innate sense. When the going gets tough, give your horse his head, so he has the freedom to watch for obstacles, and use his head and neck for balance.

Credit: Heidi Melocco Horses bred for saddle gaits are born to a legacy of surefootedness. Shown is a Rocky Mountain Horse, a smooth-gaited horse bred to negotiate the rugged Appalachian Mountains.

Credit: Heidi Melocco Horses bred for saddle gaits are born to a legacy of surefootedness. Shown is a Rocky Mountain Horse, a smooth-gaited horse bred to negotiate the rugged Appalachian Mountains.? Properly condition your horse. An out-of-shape, fatigued, muscle-sore horse is likely to drag his toes, avoid raising his feet high enough to clear obstacles, stumble, and be inattentive. Gradually build up to the amount of work you ask of your horse, especially a younger mount.

? Avoid overriding. Because you love your horse’s smooth, speedy gaits, it can be tempting to override them. Prolonged riding in gait can lead to soreness and accompanying sourness, and the inevitable rough ride and stumbling that follow. Excess speed for conditions can compromise even the surest of fleet feet.

? Immediately dismount a sore horse. Learn to recognize signs of soreness and pain, and dismount if you spot one. Such signs include lack of enthusiasm, toe dragging, and shortened or stumbled steps.

? Keep your lazy horse alert. If your horse stumbles because of laziness, periodically wake him up with a simple maneuver, such as a stop, back, or turn on the haunches. Perk him up before heading over rough trails or down steep descents. Teach him to pick up his feet by working him in an arena over cavalletti at the walk or trot, or slowly in gait.

The former editor of The Gaited Horse, Rhonda Hart is the author of Trail Riding: Train, Prepare, Pack Up & Hit the Trail.. She resides in Washington State, where she trail rides extensively.