Withers, which are formed by a section of your horse’s spinal column, play a big role in the mechanics of his movement. | © Arnd Bronkhorst

Withers, which are formed by a section of your horse’s spinal column, play a big role in the mechanics of his movement. | © Arnd BronkhorstNext time you groom your horse, take a minute to appreciate his withers. That ridge between his shoulder blades is more than the reference point for measuring height. It plays a big role in the mechanics of his movement, so much so that even small problems here can affect performance.

In this article we’ll look at some of those problems with input from Sarah le Jeune, DVM, an assistant professor and head of the Equine Integrative Sports Medicine Service at the University of California, Davis. A board-certified equine surgeon, Dr. le Jeune is also certified in equine sports medicine and rehabilitation. She focuses on diagnosis and treatment of lameness and performance problems through an approach that combines traditional medicine with acupuncture and chiropractic care.

Sore withers aren’t the most obvious cause of poor performance, so they’re easy to overlook. To understand why they’re important, begin by looking below the skin.

Inside and Out

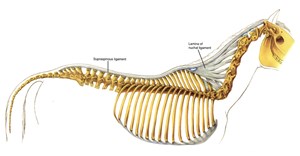

A horse’s withers (the term is always plural—there is no singular “wither”) are formed by a section of his spinal column. The roughly nine linked bones that make up this section—thoracic vertebrae numbers 3 through 11 on anatomy charts—have a unique shape. All the bones in the spinal column follow the same basic plan: a thick body with wings on each side, with an arch rising up to enclose the spinal cord and a bony spur, the dorsal process, projecting up from the arch. At the withers the dorsal processes are extra long, as long as seven inches in some cases. The tips of these processes underlie the withers.

The bones of the withers help anchor major ligaments that support the neck and back. | © Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy

The bones of the withers help anchor major ligaments that support the neck and back. | © Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine AnatomyThe bones help anchor major ligaments (bands of fibrous, elastic tissue) that support the neck and back. Among the most important is the supraspinous ligament, which stretches along the back from the withers to the croup. At the withers it blends into the nuchal ligament, which supports the neck. Muscles that flex and extend the back and neck are linked to the withers. They include the longissimus dorsi, which runs along the back, and muscles that fan out from the withers to points on the spine in the neck.

When a horse raises or lowers his head or collects his stride, he’s working at least in part off his withers. The withers act as a fulcrum, balancing the actions of the muscles and ligaments so that when the horse lowers and extends his neck, his back lifts—a mechanical action essential for collection. They also help determine his stride. The stride begins at the shoulder, which is bound to the withers and other points of the spine and ribs by layers of muscle and tendon. The way the withers and shoulders are assembled influences the length and sweep of the stride, making the withers an important feature in assessing conformation.

Trainers look for withers that are well defined and well muscled, so they blend smoothly into the neck and back. They also look for withers that are set well back behind the point of the shoulder, so the topline of the horse’s neck is perhaps twice as long as the underline. Then the shoulder runs forward from the withers at an angle that permits a full range of motion. Straight shoulders often come paired with low withers, a short neck and a long back. Horses with this conformation typically have choppy strides.

Trouble Signs

Soreness to touch, swelling and heat around the withers are clear signs of a problem. As in the rest of the back, though, sore withers can present subtle and confusing signs. Problems with performance and attitude may be the first clues. You might notice that your horse

When a horse lowers and extends his neck, the withers act as a fulcrum so his back lifts. | © Arnd Bronkhorst

When a horse lowers and extends his neck, the withers act as a fulcrum so his back lifts. | © Arnd Bronkhorst• Starts to travel with short strides or move less freely through his shoulders

• Resists collected work

• Starts refusing fences or jumping stiff and flat

• Pins his ears, swishes his tail and generally objects to saddling

• Acts “cold-backed”—sinks, humps his back or even bucks—when you mount.

These signs can be caused not only by soreness at the withers but also by pain elsewhere—in the back, legs or feet, say—or by training and behavior issues. Your horse’s vet can help locate the problem.

“A true lameness should always be ruled out as a contributing factor to pain in this location,” Dr. le Jeune says. “Cold-backed horses may have true back pain or this may be a learned behavior due to previous chronic pain. It may be difficult to differentiate between pain and behavioral issues. Gastric pain can also be a cause.” A short course of an anti-inflammatory medication like phenylbutazone sometimes sheds light. If the horse doesn’t improve on the medication, he may not truly be in pain. “If the cause is behavioral, it can be difficult to resolve,” she says.

Fortunately, one of the most likely causes of sore withers is also easy to identify and simple to fix: poor saddle fit.

Saddle Sore

Differences in conformation help make the area around the withers a common site for saddle-fit problems. Low, flat “mutton” withers can make it hard to keep a saddle stable. High, narrow “knife-blade” withers also cause saddle-fit problems, especially when the muscles on each side of the withers are not well developed.

High, narrow “knife blade” withers cause saddle-fit problems, especially when the muscles on each side of the withers are not well developed. | © Arnd Bronkhorst

High, narrow “knife blade” withers cause saddle-fit problems, especially when the muscles on each side of the withers are not well developed. | © Arnd BronkhorstThe width of the saddle tree is a key factor. “If the saddle is too narrow for the horse’s build, it puts pressure on either side of the withers,” Dr. le Jeune says. “If it’s too wide, it may put pressure on the top of the withers,” riding so low that the pommel presses and rubs the skin.

What happens: Saddle sores can progress from mild to ugly, and they can be excruciatingly painful. Your horse may be sensitive around the withers when you groom and tack him up and be cranky and resistant when ridden. His coat may rub out at the pressure points. If rubbing continues, a raw sore develops. Or, over time, white hairs appear at these points. “Pressure affects the hair follicle and decreases the pigmentation,” Dr. le Jeune explains. “Usually hair will remain white for one coat cycle. If damage to the hair follicle was severe, then it may stay white.”

What to do: Treat an open sore like a superficial skin wound. Clean it gently with sterile saline solution and topical antiseptic such as Betadine or Nolvasan and apply triple-antibiotic ointment. It’s not practical to bandage this area, but check and clean the sore daily and keep tack and blankets off until it heals. In fly season use repellant ointment around the edges.

Whether the skin is rubbed raw or not, a saddle sore won’t heal unless you relieve the pressure that’s causing it, Dr. le Jeune says. In most cases that means reflocking or replacing the offending saddle. Pads can help protect the skin and absorb some pressure, but they can’t really correct fit problems. “The padding that best relieves pressure is sheepskin,” she says. Thick pads under a saddle that’s too wide may help keep the pommel off the withers, but they won’t help if the saddle is too narrow, she adds—“just as adding more socks does not help when your shoe is too small.”

Prevent it: “Check the fit of your saddle at least once a year, but for sure if the horse has had an injury and has been laid up and lost muscle mass or has gained or lost weight,” Dr. le Jeune says. That’s important because the shape of a horse’s back changes as he gains or loses weight and muscle. She suggests an eight-point inspection (see the box on this page).

Blankets that rub the withers can cause sores, as can saddle pads that are dirty, bunched or binding. Be sure your saddle pad lies smoothly and is pulled up into the gullet a bit so that it doesn’t lie tight over the withers and rub.

Super Sore

A more serious problem can develop deeper in the withers, at the level of ligaments and bones. Here, fluid-filled sacs (bursae) cushion the tall dorsal processes, preventing the ligaments from rubbing against bone. Inflammation in these sacs causes painful swelling over the withers. The condition, which is fairly rare, is called supraspinous bursitis or fistulous withers.

Low, flat “mutton” withers can make it hard to keep a saddle stable. | © Paula da Silva/arnd.nl

Low, flat “mutton” withers can make it hard to keep a saddle stable. | © Paula da Silva/arnd.nlWhat happens: The trigger is often trauma—injury in an accident, say, or long-term use of an ill-fitting saddle or even blankets. Infection can take hold, Dr. le Jeune notes, if bacteria reach the bursa through a wound or from the bloodstream. The swollen, infected sac may rupture and drain, creating an opening (fistula) to the outside. Infection can also spread from the bursa to other tissues, including (in advanced stages) the bones.

What to do: “The earlier treatment is instituted, the better the prognosis and outcome,” Dr. le Jeune says. “The most successful treatment is complete dissection and removal of the infected bursa and prolonged antibiotic treatment.” A chronic infection or one that has spread to bone may be difficult to root out.

The vet will want to test the fluid from the bursa for bacteria. Among several types known to cause these infections is Brucella abortus, which causes brucellosis in cattle and can also infect humans. “A horse with fistulous withers should always be tested for it because of the human health risks,” Dr. le Jeune says. But, she adds, Brucella has nearly been eliminated in cattle, so it’s now rare to see it in horses.

Prevent it: Attention to saddle fit and prompt care for any injuries to the withers are the best preventive steps.

Broken Withers

Deformed withers, flattened or pushed off to a side, are typically the result of an accident that fractures the bony spines below.

When the saddle pad lies tight over the withers, it can cause rubs and sores. | © Paula da Silva/arnd.nl

When the saddle pad lies tight over the withers, it can cause rubs and sores. | © Paula da Silva/arnd.nlWhat happens: Here’s one scenario: The horse backs up on cross-ties, panics and rears, snaps his halter and is carried over backward by momentum. If his withers take the brunt of the impact, the dorsal processes may fracture. A bad trailer accident can also cause these injuries, Dr. le Jeune says, but that’s rare.

What to do: If your horse flips over or is involved in any serious accident, have the vet check him over thoroughly. He may have multiple injuries, and broken withers aren’t the most serious possibility.

Fractured dorsal processes usually heal on their own without surgery or other intervention. If there’s a wound and fracture at the withers, “The pieces of bone may become infected, leading to fistulous withers,” Dr. le Jeune says. Without that complication, all that’s really needed is rest.

If the horse is very sore at first, the vet may prescribe anti-inflammatory medication. If it’s painful for him to lower his head, hang a hay net in his stall and put his water and feed at chest height. As he becomes more comfortable he can be turned out for exercise. But the area will still be healing, so don’t rush him back to work. Count on at least three to four months of rest, Dr. le Jeune says.

The broken spines rarely rejoin. Instead, they rest wherever they lie, usually tipped to one side or the other. Once they heal, the withers won’t be painful; but they probably will be deformed—flatter and wider or otherwise misshapen. The abnormal contour may call for a special saddle or extra padding, but broken withers seldom sideline a horse for good.

Prevent it: Since flipover injuries are the main cause of broken withers, take sensible steps to prevent them. See the box on this page for some tips.

Kissing Spines

Deep muscles and ligaments stabilize the bones of the spine, but sometimes the tips of the dorsal processes touch and rub against each other. The condition is called overriding spinous processes, or kissing spines. “It’s most common in the mid-back but can occur in the withers,” Dr. le Jeune says. The length of the spines at the withers and the fact that they tilt backward increase the odds of contact.

What happens: Depending on the horse’s conformation, the spines may be too close from birth or an injury may damage the ligaments between them so that they are less stable and jam into each other. The irritation produced by contact can cause bone to erode in some areas and build up in others.

However the problem starts, work under saddle aggravates it. The horse tenses his back muscles to protect his spine, restricting his stride. He may object to mounting, buck or sink under weight.

What to do: By blocking nerves with local anesthetic, the vet can determine which vertebrae are causing pain. Treatment may include injecting a corticosteroid (to reduce inflammation) and/or Sarapin (an analgesic, to reduce pain) between the spines. Shockwave, acupuncture, chiropractic and mesotherapy (injections of small amounts of medication into the skin) can also help, Dr. le Jeune says.

These treatments can help manage the condition, but they don’t fix the underlying problem. A surgeon can remove the tips of the rubbing spines, but this is seldom done—it’s a major operation followed by a long recovery, and it doesn’t always relieve the horse’s pain. Surgeons in Britain have developed a different approach, cutting the interspinous ligament between the affected spines. This ligament links the spines about halfway up their length, and cutting may allow them to move apart. The procedure is new and not yet widely done.

Prevent it: There are no specific steps that will prevent kissing spines, but keeping a horse fit for the level of work he’s asked to do can lessen the risk of a back injury that might lead to the condition. Reducing the horse’s work level may help prevent a recurrence.

And More …

The four problems covered here aren’t the only causes of pain in the withers. Ligaments can be injured. “Supraspinous ligament injuries can be painful and require rest and possibly shockwave therapy or even regenerative medicine [treatment with platelet-rich plasma or stem cells],” Dr. le Jeune says. These injuries are less common at the withers than in the mid-back and lumbar spine, however.

Joint disease can also appear, and once it does the damage done to the joints between the vertebrae can’t be reversed. Usually the problem is managed with changes in work and efforts to keep the horse comfortable. “Acupuncture and chiropractic can be useful modalities to resolve the pain,” Dr. le Jeune says.

Saddle-Fit Checklist

Is your saddle hurting your horse? Check these points to be sure it conforms to the shape of his back and distributes your weight evenly.

Check the fit of your horse’s saddle at least once a year. | © clixphoto.com

Check the fit of your horse’s saddle at least once a year. | © clixphoto.comBalance: The center of the seat should be parallel to the ground.

Withers clearance: You should be able to fit two or three fingers between normal withers and the saddle. (Low “mutton” withers may allow a little more; very high withers, a little less.) Clearance should be all around, not just at the top. “It is important to check that there is sufficient wither clearance even with the weight of the rider,” Dr. le Jeune says.

Gullet width: The gullet should be three or four fingers wide so that it won’t interfere with the spinal processes or the muscles of the horse‘s back.

Panel contact: Panels should rest on the horse’s back evenly from front to back, not overstuffed in the middle (the saddle will rock) or bridging (with a gap in the middle).

Billet alignment: Billets should hang perpendicular to the ground so that the girth is not angled. Then the girth will always find its correct position at the sternal groove, the narrowest point behind the elbow.

Shoulder fit: Panels at the front should be parallel to the shoulder.

Tree points (the front tips of the saddle frame) should be behind both shoulder blades.

Straightness: The saddle should not tilt to one side or the other when viewed from the back.

Saddle length: The saddle should not be so long that it puts weight on the shoulder or loin area. The rider’s weight should be carried on the support area over the rib cage.

Prevent Flipovers

Most flipover injuries occur when a tied horse pulls back, feels his head restricted and panics. This is most likely with young or excitable horses, but any horse can do it. To cut the risk:

• Work in a three-sided space, closed on three sides and open in the front, where the horse can’t pull back. Use a wash stall, a grooming stall or the end of a barn aisle (with the doorway closed behind the horse).

• Be sure the floor has a textured nonslip surface, like a rubber mat.

• Attach cross-ties to facing walls at a point higher than the horse’s withers. Make them long enough to let him lower his nose to knee level but not to the ground. If he can’t lower or turn his head, he’s more apt to panic

• Make weak breakaway “fuses” by attaching loops of string or baling twine between the ends of the ties and the wall anchors or the halter snaps.

• If you must tie a horse with a single rope, use a quick-release knot so you can just pull on the end of the rope and free him.

• Don’t make sudden moves around a tied horse or leave him unattended. If he raises his head and steps back, don’t reach for his halter—that will likely send him back more. Move to his hindquarters and cluck or tap his rump to move him forward.

• If you can’t tie him safely, don’t tie him at all. Hold him or ask someone to hold him for you.

This article originally appeared in the April 2015 issue of Practical Horseman.