Weeks of cooped-up idleness can make your horse aggressive, anxious, or dull, and can even interfere with his healing, unless you anticipate and counteract the effects of confinement.

Adjust his feed to avoid energy overload. Consult your veterinarian right away about how to curtail carbohydrates, fats, and sugars in your horse’s ration while ensuring that he gets the nutrients he needs (depending on the nature of his injury) to rebuild soft tissue or bone.

A confined horse on high-octane concentrates feels physically revved up with nowhere to go; for some, this translates into vices such as cribbing, pacing, or weaving. Mentally, excess energy fuels aggression–one reason some sweet-natured horses turn hostile during stall rest.

If your horse’s grain is reduced to a handful of pellets, a recreational feeder that releases tiny amounts as he plays with it (such as the Pasture Pal or Equiball Feeder) available from many catalogues, or a homemade version using a gallon plastic milk jug with a small hole in it) gives his food added value as entertainment. There’s a hanging spherical hay feeder (the Hay Ball, available at KV Vet Supply-800-423- 8211 or on the Web at www.kvvet.com) that functions in the same way.

Give him lots of loving attention. Aside from providing basic care, many owners ignore a laid-up horse. That’s stressful for a horse who’s used to and enjoys the attention that goes with regular work. Some horses quietly withdraw as a result; others act up at first like naughty children, trying to get any type of attention–but if they get no results, they also slide into apathy. Make your horse feel valued with leisurely grooming and massage sessions, or find ways to spend time where you can talk to him–for instance, clean your tack or even work on your checkbook and accounts beside his stall.

Provide companionship. As herd animals, most horses find isolation stressful (and stress can interfere with healing); those who already suffer from separation anxiety may get so frantic without other horses in sight that they actually injure themselves in the stall.

If a different stall in the barn gives your horse a better view of his neighbors (and of barn activities in general, which will help to amuse him), try to arrange the switch.

When the others are turned out, see that at least one stablemate is in the barn with him at all times. Or, if he can’t always be in sight of another horse, find him a companion of a different species. Goats and even pigs make excellent stall buddies; some horses become attached to the stable cat.

Keep his mind (and body) active. Without the stimulation of a regular job, a laid-up horse may become mentally dulled and less responsive to his environment (the veterinary term is obtunded). Depending on his injury — check with your veterinarian before you start–there are things you can do with your horse right in his stall that stimulate his mind and his circulation as you encourage him to move around gently. (Use low-carbohydrate treats, such as peppermints–oil of peppermint is also a natural calmative–or apples and carrots as rewards.) Begin basic clicker training (see Practical Horseman’s September 1998’s “Horse Calls” for details); or work on simple ground manners, such as stepping away from a gentle touch.

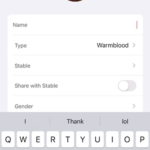

Teach him to play with one of the many stall toys available in tack shops or from catalogs. Invent your own games (again, using your veterinarian’s advice): One Warmblood I know learned to play an equine version of soccer while recuperating from Lyme disease, and I’ve taught my own horse to “dance” with me in his stall–one step right, one step left, one step forward, one step back.

Restore turnout in stages. It’s natural for your horse to want to go ballistic when he’s finally released from his stall, so when your veterinarian gives the go-ahead for turnout, ask about the advisability of tranquilizing the patient for his first couple of outings (especially if he’s normally high-strung or he uses turnout as a chance to cut loose).

For his first turnouts, use a small paddock or a round pen, where he can’t build up a dangerous amount of speed; work up to a larger space gradually. And if you’re turning him out with a companion, make sure the other horse is a quiet, unexcitable type.

Dr. Linda Aronson is an animal behaviorist and veterinarian based in the Boston, Mass., area.

This article first appeared in the October 2001 issue of Practical Horseman magazine.